The mind as an isomorphism machine

In a previous post, I enumerated a few approaches/theories about how intelligence might work.

In this post, I’ll explore my current “best” guess. Keep in mind that my “best” guess changed over time. I would consider some of my previous best guesses wrong, so by extrapolation, my current best guess is also likely to be wrong. Also, I haven’t researched this idea very much, I would not be surprised to find that I missed some existing work.

As I said earlier, the “Analogy as the Core of Cognition” idea needs further investigation. (video). This idea makes a lot of sense, the only problem with it is that “analogy” is defined very broadly: as the common essence shared between two concepts.

I think we can simplify this idea a bit and adopt a new terminology. Let’s rename concept as structure and

analogy as isomorphism. Rapid quick check on wikipedia for isomorphism:

In mathematics, an isomorphism is a homomorphism (or more generally a morphism) that admits an inverse

Not very useful. If we check the entry for homomorphism:

In abstract algebra, a homomorphism is a structure-preserving map between two algebraic structures

Very good. For our purposes, we can say that an isomorphism is just an equality (or partial equality) of structure. If we have a concept A and a concept B, we can say the two are isomorphic if they share a lot of structure.

The idea behind the “mind as an isomorphism machine” is the following: there is a lot of structure in the world, and the mind is trying to capture it. So it slowly builds an internal model that mirrors the world, in other words, a model that is isomorphic to the world.

An important detail: in this process, he mind is not trying to make sense of the world (ie, build a model) as it appears, but rather as it really is. In other words, it is modelling the true causes that are generating the observed sensory data. This explains why we have optical illusions.

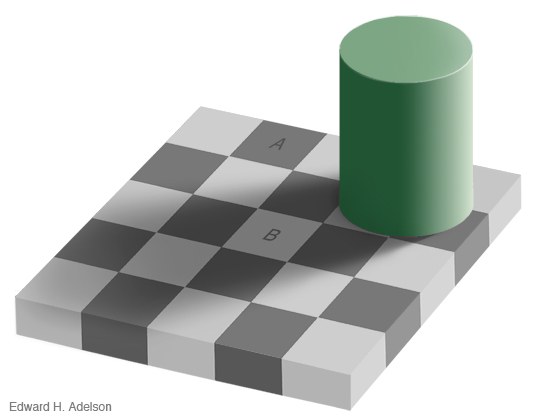

For example, take this illusion:

We see square A and square B as having a different color. But if you really check, you will find that in the image, A and B really are the same color, that is, the RGB values are the same.

But let’s ask the question again: are A and B the same color?

Well, in which context ? In the context of the image (read: sensory input data), they are the same color. But in the context of the world (the hypothetical world such that if you were to observe it, you would see the image), the two squares would not be of the same color.

Which context is more useful ? Arguably, the context of the hypothetical world is more useful, because it is very much like our own, and we want to infer things in our world, not in sensory data. Sensory data is a gateway to be able to know about the world. We ultimately care about the world and not sensory data itself.

So when we look at the image, the brain constructs a model of the elements as if they were elements of a real hypothetical world and infers the most likely causes: light sources, objects, shapes, orientations, shadows… The model-constructing and property-inferring is so good that the colors for the squares A and B are inferred as not the same - exactly as they would be in the hypothetical world depicted in the image ! A and B having the same values in the sensory data is just a coincidence.

To summarize: We see not the world as it appears, but as it really is. Our minds have constructed a model of 3d objects as they are in the world. The objects, relationships, positions, orientations are the same in the model as they are in the world: the model is isomorphic to the world.

Naturally, this model-building is not restricting to vision. It also applies to logic, social situations, intuitive psychology (theory of mind) and intuitive physics, to name a few.

Now we can see the mind as a machine trying to build models more and more isomorphic to the world. Then we define intelligence as the possession of such a model. And the greater the degree of isomorphism between the model and the world, the greater the intelligence.

I’ll leave it at that for now. I’ll explore the implications of this idea in future posts.